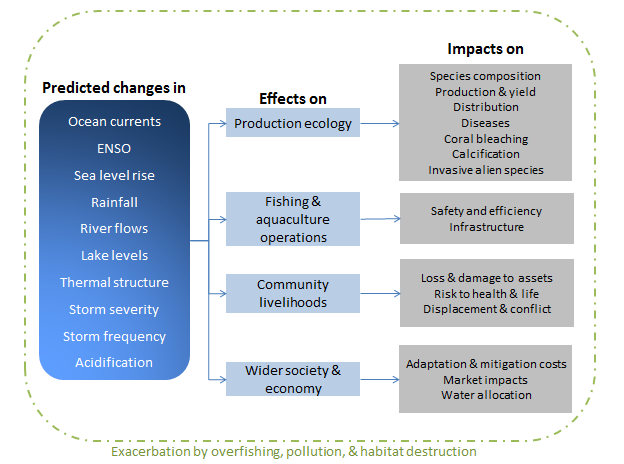

Jamaica’s fisheries sector collapsed in the 1960s, in what is often viewed as the most dramatic decline in the Caribbean region. It is a particularly vulnerable sector for a number of reasons. Direct human induced impacts include unsustainable fishing practices e.g. dynamiting, use of poison, ‘hookah’ diving, and not throwing back undersized fish, as well as coastal habitat destruction (for development). It also suffers from indirect human induced impacts such as poor water quality from polluted inland run-off, and the introduction of diseases (e.g. decimation of the black sea urchin, Diadema). Additionally the marine environment that fishing depends on has been severely impacted by extreme events (of particular note are Hurricanes Allen and Gilbert in the 1980s). These impacts in conjunction with each other have an exacerbating effect, and to complicate matters further, the impacts of climate change have been, and will continue to play a major role in Jamaica’s fisheries sector. The figure (Badjeck, 2010) below outlines potential impacts to the fishing sector as a result of climate change.

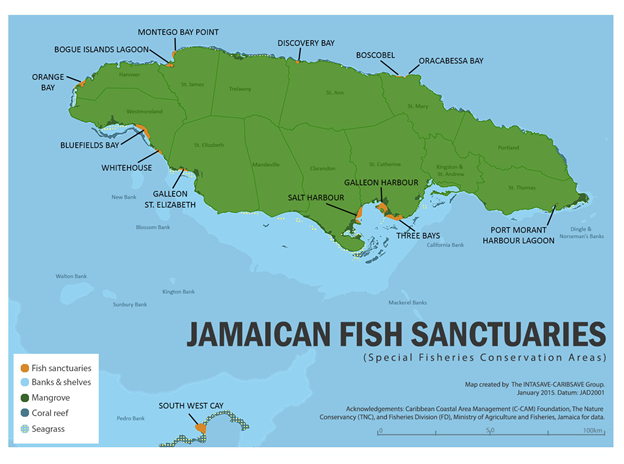

For Jamaica, these impacts and effects could be significant. For example Jamaica’s catch composition has already shifted to being mostly of low value, “trash” fish, and particularly parrotfish – a species that has been shown to play an important role in coral reef health. Low-value catches (in quantity and quality) tend to force fishers to spend longer at sea and catch more fish (leading to over-exploitation) to make their income. Another example is that Jamaica’s fishery is primarily reef fishery, and if there is migration of fish species to cooler waters, the majority of Jamaica’s fishermen are not equipped (with the gear or the skills) to fish in the deeper, cooler waters. Calcification can also potentially cause significant damage to Jamaica’s Queen Conch industry, which is a profitable economic export activity. These impacts to the fisheries sector, and to the broader coastal zone have been recognized by the Government of Jamaica, and a number of climate change adaptation efforts have taken place over the past couple years from a variety of different organizations. Legislation and Policies In Jamaica there are 52 statutes that have direct or indirect jurisdiction over matters of the environment. In particular, the Natural Resources Conservation Authority Act (1991) provides for the management, conservation and protection of the natural resources of Jamaica. This Act plays an integral role in Jamaica’s environmental regulatory requirements (prescribed by the Environmental Permit and License System (1997)), which ensures that all Jamaican facilities and development projects meet the relevant standards and procedures to minimize adverse environmental impacts as it relates to, for example, the handling effluents discharged into the environment, or the removal or sensitive coastal ecosystems. Jamaica also has a well-developed Climate Change Framework, although it does not specifically mention Fisheries, but rather groups it under the Agricultural sector. The fisheries sector has it’s own section in Jamaica’s 2nd and 3rd National Communications to the United Nations Framework for Climate Change, and has its own National Adaptation Strategy plan (albeit in its initial stages). Additionally, the latest draft of the national Fisheries Policy makes an effort to mainstream climate change into the document. Protected Areas Protecting parcels of ecosystems are commonly used as a way to conserve or increase an ecosystem’s health and thereby resilience to climate change. Furthermore, healthy ecosystems generate more ecosystem services to surrounding communities, also making them more resilient to changing environmental and economic climates. There are 6 protected areas that encompass marine zones – Negril, Ocho Rios, Port Antonio, and Montego Bay Marine Parks, as well as the Palisadoes-Port Royal and Portland Bight Protected Area. In addition to these protected areas the Government of Jamaica has, to date, established 17 Special Fishery Conservation Areas (SFCAs) around the island, including one on the Pedro Bank. Unlike the marine protected areas above, SFCAs prohibit fishing alone and offer no direct protection to marine ecosystems. However, indirectly they are preserved, as they are not inadvertently damaged from fishing practices such as damage from nets dragging. These SFCAs operate under a wide variety of management styles, effectiveness, funding, and ecosystem availability. As such, the success of each is also very varied, but many are showing good results. The most iconic to date is the Oracabessa SFCA which demonstrated approximately 1500% increase in fish biomass over 3 years. The success of these SFCAs and protected areas is also demonstrated in a non-quantifiable manner. For example, many of these protected areas are the sites of local and internationally funded interventions that provide capacity building and alternative livelihoods for the community. Whether it is these benefits, or that fishers are genuinely seeing increases in fishing resources, many communities nearby existing SFCAs have expressed interest in establishing their own.

Photo: The location of Jamaica’s Special Fishery Conservation Areas (SFCAs). Note, the 3 most recently established, i.e. Boscobel East, Boscobel West (in St. Mary) and Alligator Head (in Portland) are not shown here. ‘Grey’ Adaptation Historically, physical changes to beaches triggered the installment of engineered, hard structures (‘grey’ structures) such as groynes, to prevent further erosion, or to help the beach accrete. One such example in Jamaica is the installment of several Wave Attenuating Devices© in Old Harbour Bay – a popular fishing village in Jamaica – to help prevent further erosion. Anecdotal evidence suggests there has been some success on this front.

Photo: The Wave Attenuating Devices (WADs) in Old Harbour Bay, installed to help mitigate the severe erosion being experienced by the fishing users of the beach. In another south coast location, several EcoReef© units were installed underwater within the SFCA boundaries to act as an artificial reef habitat for an otherwise habitat-limited environment (the SFCA is comprised mostly of seagrass beds). Another structure, serving a similar aggregative purpose to the EcoReefs, is the experimental lobster condominiums (sometimes referred to as ‘casitas’) by the Fisheries Division. These too provide a safe haven for juvenile lobsters prior to their migration reef areas.

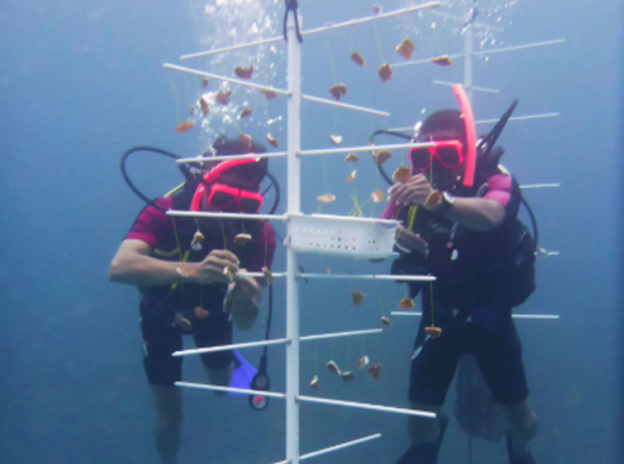

Photo: The EcoReefs provide a complex environment for young fish to shelter prior to their migration to larger reef areas. They also have the potential to act as substrate for coral restoration. ‘Green’ Adaptation Much debate surrounds the use of ‘grey’ infrastructure versus ‘green’ infrastructure, which more typically involves enhancement of the protective services that ecosystems provide. For example, a healthy mangrove forest can help prevent storm damage by reducing wave height and power, reduce erosion and can even help counter sea level rise. ‘Grey’ adaptation measures are typically frowned upon when the structure in question is something large and permanent e.g. groyne. There are numerous examples of engineered structures causing the wrong impacts or inadvertently causing negative side effects (e.g. creating ‘dead zones’ in bays). Additionally the capital investment needed for these structures is high, particularly for fishing communities. In reality, a combined ‘grey’ and ‘green’ approach is probably most suited for adaptation efforts when considering costs, timeframes and side benefits. Jamaica has undergone several pilot programs in ecosystem-based adaptation to climate change, focusing on coral and mangrove restoration. Coral restoration has typically used the Acropora species as being fast growing, reef building species. So far, the majority of the coral restoration work has been done in protected areas, namely Negril, Discovery Bay, Boscobel, Oracabessa, Whitehouse and Bluefields Bay. Different approaches have been used by different agencies, but typically require the hiring of ‘coral gardeners’ to help, thereby providing a form of secondary income to a community member. Results have been mixed, particularly given the short time frame, but they are showing good initial results.

Photo: Coral gardeners string fragments of Acropora palmata onto a tree style nursery. Restoration of mangrove forests has also been explored in, for example, the Portland Cottage area which is typically savaged when storms or hurricanes pass through Jamaica. In this area, hydrology was examined and altered and significantly improved growth of existing mangrove stands, as well as having a positive effect on recruitment of seedlings. The University of the West Indies has also undergone a mangrove nursery program, offering seedlings for restoration activities.

Photo: An experimental mangrove restoration activity in the Portland Bight Protected Area using natural fibre cells to retain sediment. In conclusion, although faced with numerous challenges, Jamaica’s fisheries sector has been making strides in the right direction to making it more resilient to climate change. Many of these efforts are pilot projects that if successful, should be replicated on larger scales. In other instances there is opportunity to take lessons learned, not only from national projects, but other international ones, that can guide future adaptation and mitigation activities. Some of the main priority activities for improving climate change adaptation in fisheries includes the provision of supplementary livelihood options for fishing villages, increasing the ecosystem approach to adaptation, capacity building for fisheries management at the governmental and local levels, and the collection of data specific to the impacts of climate change on Jamaican fisheries, to help guide future management decisions. Although the road is long, the sector has support from numerous governmental, non-governmental, private sector, national and international agencies. With assistance from these, it is hopeful that the fisheries sector in Jamaica will recover and improve over the coming years.

References: Badjeck et al., 2010 – Impacts of climate variability and change on fishery-based livelihoods. Marine Policy 34: 375-383 Climate Change Policy Framework, Jamaica (2012). Ministry of Water, Environment, Land and Climate Change. Draft Fisheries Policy (2008). Ministry of Agriculture And Lands Fisheries Division. Retrieved from http://www.moa.gov.jm/Fisheries/data/DRAFT%20FISHERIES%20POLICY%202008.pdf Hardt, M.J. (2009). Lessons from the past: the collapse of Jamaican coral reefs. Fish and Fisheries 10:143-158. Murray, A. and Aiken, K. (2006) Artisinal fishing in Jamaica today: A study of a large fishing site. Proceedings of the Gulf and Caribbean Fisheries Institute 57: 215-234 NEPA, 2014 – Results of Coral and Fish Surveys at Oracabessa Bay fish sanctuary. Spalding M, McIvor A, Tonneijck FH, Tol S and van Eijk P (2014) Mangroves for coastal defence. Guidelines for coastal managers & policy makers. Published by Wetlands International and The Nature Conservancy. 42 p Photo credits: S. Lee, D. Campbell, D. Hughes, O. Day, M. McNaught Author: Simone Lee Acting Manager, Environmental Consultancy